Book Review: Gamblers, Fraudsters, Dreamers & Spies: The Outsiders Who Shaped Modern Japan

Author unveils treasure trove of hidden stories about postwar Japan. Robert Whiting captures underworld figures, other colorful 'outsiders' of era.

Published in Nikkei Asia

By Stephen Mansfield

In the introduction to his new book, author Robert Whiting focuses on a range of foreigners who he says have been "heretofore unknown or vastly underreported." He is right. How many people, even among well-versed readers of works on Japan, have heard of restaurateur Johnny Wetzstein, who offered all-American hamburgers and an upstairs room catering to more sensual appetites; the bellicose inebriate, Vladimir Granby Auscus, a yakuza-affiliated gangster and former White Russian; or Charles Kades, a high-ranking official in the U.S. Occupation hierarchy, who, while conducting postwar reforms under General MacArthur, was also conducting an affair with a married Japanese viscountess?

This is where Whiting's book, "Gamblers, Fraudsters, Dreamers & Spies: The Outsiders Who Shaped Modern Japan," comes in. Even in a tome of wide scope at nearly 400 pages, there are bound to be omissions among Whiting's selected gallery of villains, undercover agents, con artists, manipulative hostesses, and occasional philanthropists.

A case in point would be the late writer Donald Richie, who receives little more than a passing mention, when he comes briefly into the orbit of one of the principal players in the chronicle. Although Richie has been widely praised for his numerous books and deep insights into Japanese culture and society, Whiting's subjects are men and women of action, notable movers and shakers. The omission of people like Richie may be attributable to the fact that they were figures who, rather than influencing Japan, influenced our way of thinking about Japan.

The Japanese are not encouraged to inquire too deeply into their own history. That task has often fallen to respected foreign historians such as John Dower, or incisive cultural commentators such as Ian Buruma and Norma Field. One recalls that the first Allied military arrivals in Tokyo after the war noted the sight of smoke rising from chimneys and bonfires as wartime officials desperately burned incriminating documents. Memory cannot be incinerated, but the Japanese have been adept at burying it.

An accomplished journalist, historian and biographer, Whiting expresses reservations about the more malign aspects of the U.S.-led occupation of Japan. These included its particular brand of entitlement and duplicity, one that ranged from the "sale of a simple case of booze to large-scale operations that moved millions of dollars a year in black-market goods and dollar currency," its activities covering the "entire spectrum of morality -- or immorality."

Left: Ted Lewin, a promoter of casino gambling in the postwar era. Right: Charles Kades, a stellar GHQ figure, with his mistress, Viscountess Tsuruyo Torio.

He is unsparing in describing the Occupation's first wave of U.S. servicemen, their sense of entitlement and loutish behavior, but cannot conceal his affection for some of its feistier rogues, the brash and derring-do freebooters, or for the "free-spirited lawlessness that marked the early postwar era."

Whether they respectfully applauded the host culture was not always a given. Of Jack Canon, head of the Canon Agency, a clandestine Occupation-era organization tasked with carrying out black operations, Whiting describes a man capable of turning his Tokyo garden into a private firing range. He would strip down to his underpants and do workouts in front of his Japanese maids, "punching sandbags in the second-floor corridor."

Tokyo’s Shibuya Crossing, as it was in 1952.

In this new, postwar social order, it was an age of opportunism where identities became fluid. A thug might become an art specialist; a U.S. General Headquarters officer, a black marketeer. Whiting notes that whatever illicit activities involved foreigners, they were not, as they say in police circles, "acting alone." For every crime committed by an expat, he writes, "there were also Japanese partners involved, eager to cooperate, eager to share in the booty."

The ersatz American entertainment business, a modern floating world of bowling alleys, strip shows, bars and brothels, conducted at establishments like the Queen Bee and the Latin Quarter, greatly appealed to Japanese males. Whiting notes the irony of a transplanted American culture that "Japanese men could embrace with a passion they could not muster for other American innovations like, say, equal rights for women."

GIs and Japanese women at a party in 1945. (Courtesy of David Stetson)

A Japanese cast of politicians, shadow figures, fixers, and opportunists stand, like a Greek chorus or gathering of the Furies, in the background to Whiting's central characters. Common interests led to unholy alliances of complicity. Japanese and ethnic Korean yakuza were enlisted by politicians to suppress left-wing demonstrations. The Central Intelligence Agency, using an unsavory intermediary named Yoshio Kodama, would contribute a million dollars a year to the coffers of the ruling Liberal Party, with the funds earmarked for anti-communist, anti-leftist activities in the wake of the Occupation's end.

Freshly out of Sugamo Prison, Nobusuke Kishi, deeply implicated in forced labor programs and narcotics trading in Japanese-occupied Manchuria during the war, rose, with the help of the CIA and the notorious Kodama, to become prime minister in 1957. His grandson, Shinzo Abe, would expend much time and effort to rehabilitate Kishi's image. Abe would be assassinated in 2022 by an incensed assailant who held him accountable for his family's financial ruin at the hands of an Abe-endorsed religious group, the Unification Church, an organization the author holds up to close scrutiny.

The foreign-run Latin Quarter, a tony dinner club, photographed in 1952.

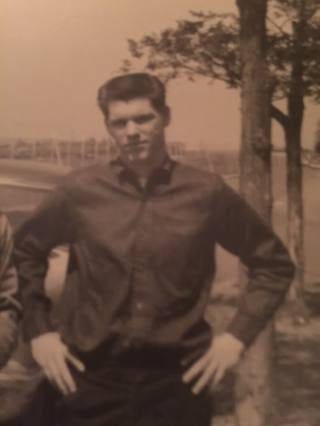

Whiting enters the story in 1962, arriving in Tokyo at the Elint Center, an electronic spy facility, as a 19-year-old serviceman.

Whiting dwells at length on the Tokyo night scene. He is sympathetic toward Japan's much-maligned club hostesses, who played a key role in the roaring business sector until the bubble economy imploded in the 1990s. The willingness to pay large sums of money to be flattered and pampered by a woman half your age might strike most Westerners as pathetic, at best, but Whiting lends an attentive ear.

A young Whiting at the Fuchu Air Base in 1964.

One Ginza hostess describes the overworked Japanese salaryman and his craving for a role-altering stage between office and home: "We try to provide a kind of nursery service, so they can revert to childhood. We're more like child psychologists than anything else," she explains.

Whiting is known for his colorful explorations of Japan's criminal underworld, stretching back decades. "People who live on the edge of society are always more interesting to read about, in my opinion, than those who operate in the mainstream," he says. That means that an embezzler with a clever scheme and a winning personality will always be more intriguing than a successful stockbroker with an adorable family and well-stocked wine cooler.

Whiting is also the foremost foreign writer on Japanese baseball, and his book includes some of the sport's most colorful and outstanding characters. He describes the legendary player Sadaharu Oh, hitting a record 55 home runs in a single season.

Whiting, center, speaks with Japanese baseball legend Sadaharu Oh in 2005.

He applies his prodigious knowledge of the sport and humanistic brand of journalism to the case of Bobby Valentine, the firebrand manager of the Chiba Lotte Marines. Valentine was the first American manager to steer a team to triumph by winning the Japan Series in 2005. Like other successful outsiders, he was widely deemed to have overstepped his role, becoming the victim of a nationalist-infused Japanese power structure and vindictive defamation campaign. It is a story that Whiting, an investigative journalist with the incisive wit of the late columnist A.A. Gill and the flair of noir novelists like Frank Gruber and James Ellroy, relates with his trademark sugarcoated toxicity.

Carlos Ghosn, the “most successful foreign executive in Japanese history.”

Whiting also profiles the ex-Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn, accused on multiple counts of swindling, personal gain and misappropriation of funds. Most readers will be familiar with the story as a result of extensive media coverage. But in Whiting's telling, the grueling legal process and the subsequent drama of Ghosn's dramatic escape from a Japanese prison, putatively to avoid a rigged justice system, reads like a fresh news item.

The author concludes that Ghosn was the victim of a particularly Japanese form of closing ranks, targeted because he "promoted a merger that would have cost a Japanese carmaker its special 'identity,' so the authorities manipulated the law in the interests of societal goals."

A difficult book to categorize, though a "social-political history" would do for starters, "Outsiders" ultimately stands alone, joining a slender number of works on Japan that are distinguished as much by their quality and journalistic integrity, as the puissant, red-blooded personalities that inhabit them. In combining the research skills of a seasoned investigative journalist and contemporary historian, Whiting has created a masterpiece of collation and in doing so, has performed a valuable service by giving exuberant life to a neglected, underreported era in postwar Japan history. As a writer of inordinate energy and perspicacity, he convinces us that books and human narratives still matter.

"Gamblers, Fraudsters, Dreamers & Spies: The Outsiders Who Shaped Modern Japan," by Robert Whiting. Tuttle Publishing (2024)