Flags of Our Fathers: Iwo Jima eyewitness tells it in his own words

Guest Post

By Mark Schreiber

TOKYO — The great Mark Schreiber provides us with a guest column from the past — a review he wrote of a piece in the popular Japanese weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun from 20 years ago about a Japanese survivor of the battle of Iwo Jima who wrote a book about his experience. Mark has been on intimate terms with the Japanese media for over 40 years and has written extensively about it. This the first of what we hope will be more guest columns featuring Mark’s work.

Flags of Our Fathers: Iwo Jima eyewitness tells it in his own words

"The Iwo Jima Memorial at Arlington Cemetery. The photo showing six U.S. Marines raising the Stars & Stripes on Mt. Suribachi was not only staged, but the summit was retaken twice by Japanese forces, who raised the Nissho-ki (Sun flag) in its place. A young Japanese serviceman who witnessed it all recounts his memories from 61 years ago." (Shukan Bunshun (12/14/2005)

Actually, the USMC Iwo Jima Memorial stands in Rosslyn, Virginia, near, but not within the boundaries of, Arlington Cemetery. And allegations that AP cameraman Joe Rosenthal "staged" the famous flag-raising photo have been thoroughly debunked.

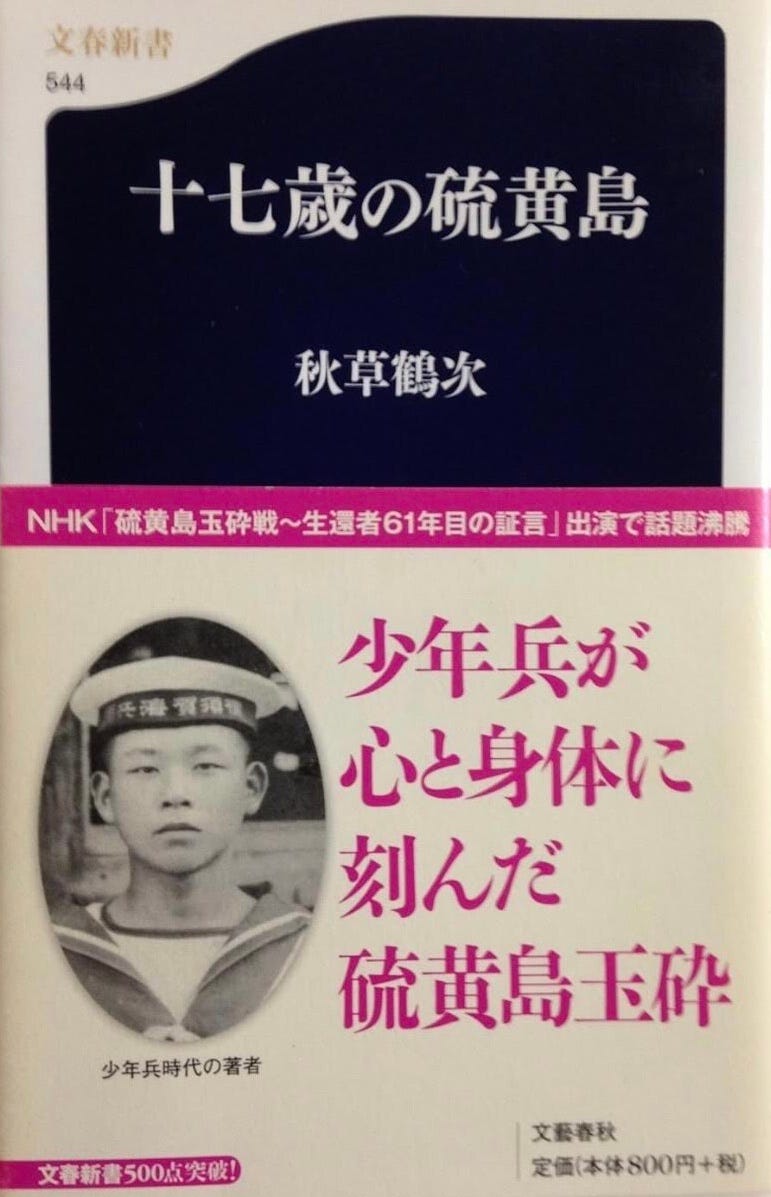

Following this partially inaccurate lead-in, Shukan Bunshun introduces Tsuruji Akikusa, age 79. In 1944, the 17-year-old Akikusa was dispatched to Iwo Jima as a signalman for the Imperial Japanese Navy. He had enlisted two years earlier following his school graduation.

Akikusa points to a photo in a movie program showing actors portraying American GIs sitting on a patch of grassy turf.

"That would have been impossible," he scoffs. "After the naval bombardment, there wasn't a blade of grass left on the island."

Out of a total Japanese garrison of 21,000 men, only 1,023 men survived, including Akikusa. He was seriously wounded during the pre-invasion bombardment in February 1945 and did not take part in the fighting. Found unconscious in the battle's aftermath, he was evacuated to a hospital in Guam and repatriated the following year.

In "Junana-sai no Io-to" (a 17-year-old on Iwo Jima, Bungei Shunju, ¥840), his personal memoirs released this month, Akikusa provides a rare eyewitness perspective of what happened on Mt. Suribachi from the opposing side.

Suribachi, the highest point on the island, harbored about 2,000 Japanese defenders. Akikusa himself was situated at a communications post some 3.5 kilometers to the northeast, on a lower peak called Mt. Tamana.

On the morning of February 23, he saw the first U.S. flag go up on Suribachi's peak, followed shortly thereafter by the second, larger flag, the raising of which was immortalized at 1/400th second in Rosenthal's famous photograph. Akikusa's descriptions up to this point correspond completely to American accounts of the event. But what followed afterward appears to contradict the official U.S. Naval version of the battle.

The following morning, as Akikusa relates in his book, "It was not the Stars & Stripes, but the Nissho-ki (Japanese Sun flag) that was waving. Even though the peak was the target of attack from every direction on the island, I thought how hard they must have fought, and tears naturally came to my eyes. The valiant fighters were defending Mt. Suribachi to the death."

The U.S. troops quickly hauled down the Japanese standard and replaced it with their own flag. But early the next morning, February 25, "the Nissho-ki was once again fluttering in the morning sunshine. It was a dazzling, beautiful sight."

"The flag was a different one from the day before," Akikusa recalls. "It was a smaller one, and square. It may have been improvised. The red circle in the center looked brownish, so it could have been blood."

"It may have been made out of a shirt. It moved me to tears. 'Our guys are still up there,' I thought. 'They're giving everything they've got. So will I.'"

"I had hoped to see the Nissho-ki still flying the next morning, but that miracle was not to be," Akikusa writes. "I said to myself, 'Well, I guess that's the end of it.'"

By March 8, the US attackers had turned their overwhelming numerical superiority on Mt. Tamana. Akikusa, wounded in the left leg and right hand, witnessed scenes of incredible carnage. Unconscious from multiple wounds, he awakened in a POW hospital on Guam.

Repatriated after the war, Akikusa called on the families of comrades killed in the fighting. But his visits were not necessarily welcomed.

"Their reactions were about half positive and half negative," he relates. "Many of them told me, 'We've already completed our Buddhist memorial services.' I guess they wanted to put it behind them as quickly as they could."

Shukan Bunshun asks Akikusa if he felt deaths of his comrades in arms was meaningful.

"Considering how this country has been without war for the past 60 years, I think it's commendable," Akikusa replies. "If you regard them as 'sacrificial pawns' who caused Japan to relinquish what it sought to become in those times, then I want to believe their deaths were not without meaning."

+++

Here is another. Hitler Youth in Japan

Hitler Youths' three-month sojourn in Japan in 1938 largely forgotten

Japan was one of the three major signatories of the Tripartite Pact that formed the basis of the Axis alliance. The pact, between Japan, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy was inked with much fanfare in Berlin on September 27, 1940.

Four years earlier, on November 25, 1936, Germany and Japan became the first signatories of the Anti-Comintern Pact, an agreement directed against the Communist International (Comintern). It also contained a secret additional protocol that specified a joint German-Japanese policy specifically aimed against the Soviet Union.

Following the holding of the 11th Olympiad in Berlin in August 1936, Germany supported Tokyo's bid to host the next Summer Olympics, in 1940. This set the stage for more people-to-people exchanges, one of which was a 90-day goodwill visit to Japan by 30 members of the Hitler Youth.

Although a major news story at the time, the story has largely been forgotten today; but the May issue of Jitsuwa Knuckles (May 2018) serves up a reminder, with text accompanied by 10 black-and-white photographs.

The Hitler Jungend, by the end of the 1930s, was the sole youth movement to which Germans between the ages of 10 to 18 years were permitted to belong. It eventually boasted a membership of 7.7 million.

The all-male contingent of 30 members of the flower of Aryan youth arrived at Yokohama Port on August 16, 1938 for a three-month sojourn. The group was headed by Fuehrer der Fahrt (chief guide) Reinhold Schulze and Stellvertretender Fahrtfuerer (deputy leader) Rolf Redeker.

The group's first official act, on August 17, was to pay respects at the Yasukuni Shrine, where the members appeared decked out in military-style uniforms consisting of navy blue rider's trousers, black riding boots and white leather Sam Browne belts. The same day they paid courtesy calls to the Minister of Education, Army Minister and the German Embassy, which at the time had been located at the present site of the National Diet Library in Chiyoda Ward.

The group spent the evening of the 20th camping in the foothills of Mt. Fuji, where they sang songs around the campfire. The next day they climbed Japan's highest mountain to its summit.

During their sojourn meetings were arranged with members of the imperial family, leading government figures, high-ranking members of the Japanese military, priests at temples and shrines, sumo wrestlers, sword makers, students and others.

Among the photos in Jitsuwa Knuckles is a scene of two smiling Hitler Youth marching down the street in Karuizawa, as they exchanged stiff-armed *Hitlergrussen* (Nazi salutes) with local inhabitants lining the roadside.

Perhaps the most bizarre photo of all, also taken at Karuizawa, shows a grinning Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoue joining hands with two uniformed Hitlerjungend in a ring-a-ring-o-rosies circle dance.

After visiting the Toshogu in Nikko the group spent about a week in Hokkaido, and on the return leg visited Aomori, Iwate, Sendai City and Akita. Back in Tokyo, they made a courtesy call to an Army hospital, saw demonstrations of traditional martial arts and visited the Dewanoumi sumo stable, where they posed for a photo with grand champion Musashiyama and two attendants.

On November 12, a sendoff party was held at Kobe's Oriental Hotel, at which the young Germans and their Japanese hosts posed in a group photo, flanked by huge national flags bearing the Hinomaru (sun) and Hackenkreuz (swastika). The next day they boarded a vessel for their return voyage.

Less than 10 months after the group's departure from Japan, Germany would be at war with Poland. It is uncertain how many of the young Germans survived the next six years of war.

Today, that 1938 visit by the Hitler Youth has largely faded from people's collective memory. Was it because it had been a reminder of the ways in which nationalistic bureaucrats in the Japanese and German governments devoted much of their time and effort to an endeavor that ultimately turned out to be meaningless? Even if so, Jitsuwa Knuckles concludes, it was something that needs to be remembered.

Autographed copies of Robert Whiting’s books are available for purchase. These include Gamblers, Fraudsters, Dreamers & Spies, You Gotta Have Wa, Tokyo Underworld, The Meaning of Ichiro, Tokyo Junkie, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat. If you are interested in purchasing a book, please send an email to: robertwhitingsjapan@gmail.com