Fourth in a five-part series

TOKYO — The world of the 90-day hostesses was not commonly known to most ordinary Japanese citizens. But that all changed when a young English hostess named Lucie Blackman, working in Tokyo, suddenly disappeared and the subsequent investigation and media coverage exposed this aspect of Tokyo night life's dark underbelly.

Lucie Blackman was a bright, attractive 20-year old from a middle class family in England. A flight attendant with British Airways who had flown the London-Moscow route, she found such work low paying and dull and had quit the airline in the summer of 2000 to come to Tokyo, where she had heard there was a fortune to be made for English-speaking Caucasian blond women like her in Tokyo's clubs. It was her plan to spend three months there, then return home to her family in England to start thinking seriously about her future.

She entered Japan in June on a tourist visa, accompanied by another young English woman named Louise Phillips with whom she would share a small apartment in Yoyogi. The two women found hostess employment at the Roppongi club Casablanca, a small living-room sized affair with deep, cushiony sofas. It was located in a modern, new six-story building which also housed the notorious "Seventh Heaven" — the largest strip club in the city, known for its lap dances and other emoluments supplied by blonde Russian girls and Las Vegas hookers.

Described by friends as "sweet, trusting, likable," she was quoted as saying after her first few days on the job, pouring drinks and "flirting a little" with Japanese businessmen two and three times her age, "I can’t believe I'm being paid for doing this." She even found a boyfriend, an American sailor from Yokosuka.

Lucie had been on the job for about a month when one day she took off for an afternoon drive to the seashore with a client, telling her roommate that she would be back in time for an evening dinner date. She did not return.

Twenty four hours later, however, Lucy still hadn't returned. Louise went to the Azabu Police Station. Officers there sympathized, but told her no investigation could be launched until there was some evidence of foul play. After all, they said, as Louise must surely be aware, many young girls disappeared for a period of time with male friends. They noted that, after all, Lucy was a gaijin cabaret hostess and people in her profession were known to do strange, unpredictable things, especially when they might be in the country illegally. Next, Louise went to the British Embassy, but diplomats there were not much help either. Then, Louise received a strange phone call. A Japanese male speaking in broken English told Louise that Lucie was undergoing voluntary training in a religious center and would not be back for a while. But not to worry for Lucie was fine.

Click.

Louise immediately called Lucie's father in England, who got on the next plane for Tokyo.

Tim Blackman, spent several days going back and forth with the police who were conducting an investigation but were also operating in their standard don't-bother-us mode. So Lucie's father, in frustration, turned to the media. He held a high profile press conference at the British Embassy and, at the same time, managed to collar British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who was in Japan attending the G-8 summit in Okinawa. Blair, in turn, appealed to then Prime Minister of Japan Yoshiro Mori, who, in turn, was able to kindle a new spirit of cooperation in the MPD.

Heretofore, the authorities had maintained that they were unable to get any information on the phone call made the evening Lucie disappeared because it was technically impossible to trace calls made on cell phones. After the Blair/Mori entreaties, however, the police magically discovered the technology to trace such communications. They also found it within themselves to beef up their investigative force that in time it would match that in scale and intensity their probe into the 1995 subway sarin gas attack, in which members of a fanatical doomsday religious cult poisoned morning rush hour commuters.

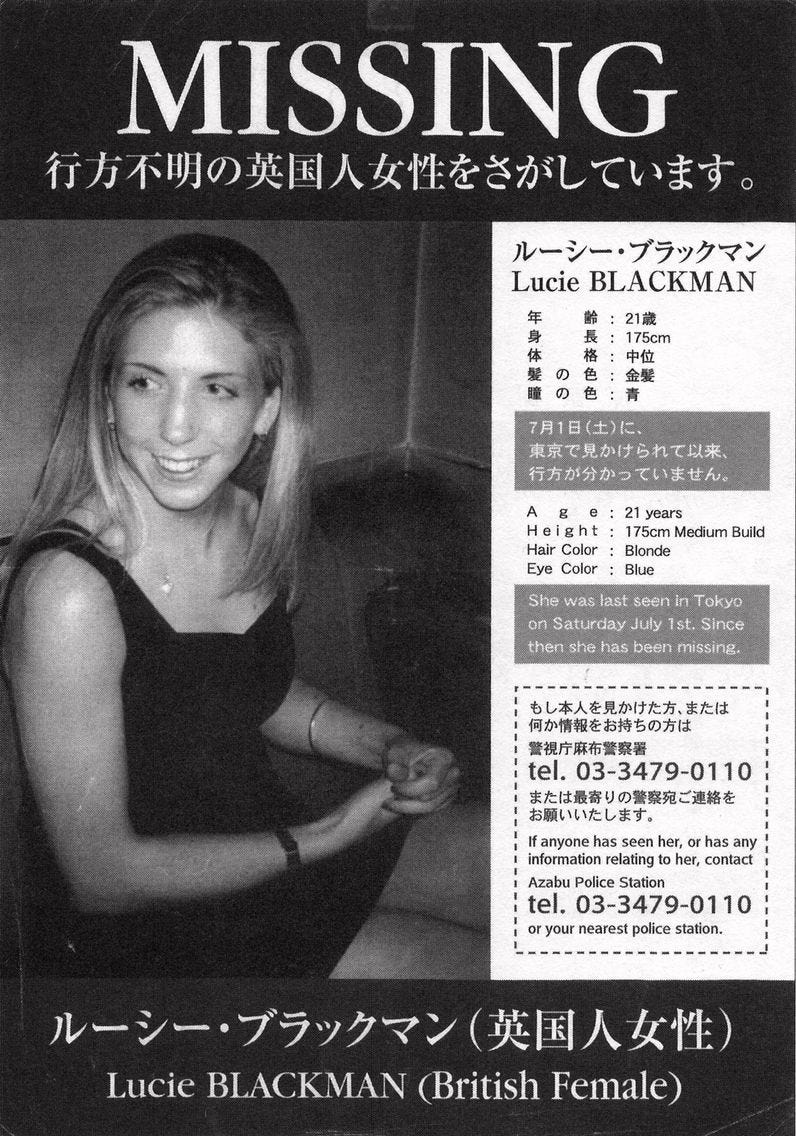

Blackman also mounted his own personal investigation to find his daughter. He distributed 30,000 missing person leaflets with the help of his oldest daughter Sophie. He rented an office, set up a hotline and even contacted yakuza figures, hoping that someone associated with the underworld might have a clue about his daughter. For the next two months, from August to October, all concerned parties waited in vain for a break in the case, Not a rich man by any means, he offered a reward of 1.5 million yen for news of Lucie's whereabouts.

A wealthy British businessman, hearing of Blackman's difficulties, independently put up his own substantially higher reward.

Lucie's father became widely recognized around the nation after holding eight separate press conferences. But not everyone in Japan was sympathetic to Blackman’s plight. One reader wrote a letter to a newspaper saying that Lucie had gotten what was coming to her for working in a place such as the Casablanca, which was hardly a bastion of moral probity. Another writer commented that if she purposefully took such a job without a work visa and other papers, then she should have expected what she got.

The American gang member in Roppongi known as Smoky had this to say: “I think that her problem was that she started to get too involved with her customers. The smart girls come to work, serve their drinks, smile, act stupid and go home at midnight. They don't accept favors or gifts or after hours dinner dates from customers — especially from the yakuza type. That's the road to trouble …”

In fact, most of them out and out refuse to sleep with a Japanese man no matter how much they offer, which when you think about it is race discrimination, but that's the way it is. Look at all the night clubs in this city that won't let Americans in."

In November, the name Joji Obara surfaced.

Obara was a wealthy 48-year-old real estate investment company president who had been arrested that month on suspicion of molesting a Canadian bar hostess in an incident that had taken place four years earlier. The hostess in question, had, at the time, failed to report the case, afraid that the police might not cooperate given the type of work she was doing and the fact of her illegal visa status. But then she heard about Lucie Blackman’s disappearance and decided to relate her experiences to Lucie’s father via his special hotline. Blackman relayed the information to the police who issued an arrest warrant for Obara and searched his Tokyo home, seizing a truckload of evidence, which included several dozen homemade videos of the defendant in assorted lewd acts with various Caucasian women, most of whom, it appeared, (and was later confirmed) had been drugged. They also found detailed journals Obara had kept of his foreign conquests, more than 50 women in all, as it turned out, along with descriptions of assorted pharmaceuticals.

To some observers, Obara was symbolic of the Bubble-Era excess that marked Japan. Son of a Japan-born Korean father who overcame discrimination to become the enormously wealthy owner of a pachinko parlor chain, he had used the family money to become a real estate speculator. However, when that venture failed, his firm, according to reports, became a money-laundering front for the Sumiyoshi-rengo-kai crime syndicate, which provided him with a substantial income. Obara, fluent in English, was fond of fast, flashy foreign cars — Ferraris, Maseratis, Rolls Royces — and, it was said, he was obsessed with blond Caucasian women, the company of which, he believed, gave him a certain cache among his peers.

The Shukan Post, in a long series about Obara published that autumn, reported he had plastic surgery on his eyes to make them look more Western, took quack growth hormones and wore lifts to extend his 5'8" height (even though he was still left a couple of inches shorter than the long-boned Lucie).

Foreign hostesses subsequently interviewed by police told of how loaded with cash Obara was and how willing he seemed to be to help them out with anything they might need — from finding a new apartment to getting a working visa. One woman reported an incident involving a fellow hostess, who said she had been taken by Obara to an upscale beachside condominium in Zushi, Kanagawa, (where the alleged molestation of the aforementioned Canadian woman took place) and drugged. A raid of the Zushi seaside premises found hair strands (including those of a blond coloring) of more than 10 different Caucasian women.

A male acquaintance of Obara was quoted by the Post as saying he knew of at least six hostesses who disappeared after they started dating Obara, and that Obara believed that none of the women would ever report anything to the police because of their illegal visa status. (Another woman, an Australian, who had a similar narcoticized encounter with Obara, discovered that the police had identified her in one of the videotapes and had sent a copy to her hometown — without telling her. She discovered the tape’s existence when her hometown authorities telephoned to inquire about her welfare.)

In weeks of interrogation, Obara admitted nothing, insisting all the accusations against him were groundless, except for one assault. But neighbors in Zushi, told police, they recalled seeing Obara one night, around the time of Blackman's disappearance, trying to change the lock on the empty apartment adjoining his. He was spotted with his hands covered in concrete and returning from a nearby beach carrying a shovel. Earlier that month, it was discovered he had paid out millions of yen in cash to buy a motorboat, without even inspecting it beforehand, inviting speculation about what sinister use he had put it to.

By February, police had charged Obara with five copycat rapes of foreign women —Canadian, British, Australian, among them — and also with the murder of an Australian woman named Carlita Ridgeway. According to the police, Obara had taken her home, plied her with drug laced drinks until she lost consciousness and then raped her. When he was unable to rouse her, he picked her up and dropped her off at the nearest hospital where the woman died a few days later. The cause of the death was a drug overdose (or more specifically, something called "hepatic failure"), which resulted in the murder charge.

Shortly after that, authorities found the dismembered body of a blond Caucasian woman buried in a cave near Obara's Zushi residence. The body had been cut into eight pieces and the head shaved and entombed in cement. DNA tests revealed it was Lucie Blackman. Police believed that she had died of an overdose in Obara’s apartment as well.

Obara was initially acquitted of Blackman’s rape and murder in a lower court due to a lack of direct evidence, but convicted on appeal in a higher court on charges of abduction, dismemberment and disposal of Blackman’s body. He was sentenced to prison for life. The case was recounted in an excellent book by the Times of London reporter Richard Lloyd Parry, published in 2011.

In the end, the remarkable thing about the Lucie Blackman case aside from the grisliness of Obara's crimes (he would later be charged with three more rapes) and the heartache it brought the Blackman family, was the media coverage and the impact it had on the public consciousness. Over the course of the several months it took for the case to unfold, there were reams of stories in Japanese about Lucie, which made Lucie's face familiar to everyone in the country. Japanese TV, radio and print commentators analyzed the story from every conceivable angle — racial, sexist, legal, moral — trying to figure out what it revealed, if anything, about the Japanese psyche.

Did Japanese men have an unhealthy attraction to blond Western women?

Was Japan becoming an immoral country.

Did Japan really discriminate against foreigners?

The English language press did its share of theorizing as well. In a breathless, grandioise cover story in Time-Asia, for example, a writer equated the Lucie Blackman case to nothing less than a national wakeup call for Japan, terming Lucie “the poster child of a nation that was suddenly unaware of where it was going and of what was happening to it,” and the case "synonymous with millennial Tokyo's anxieties, aspirations and insecurities …"

The fact that Obara lived in a multimillion dollar suburban Tokyo mansion that had gone to seed in the wake of the deflated bubble and moribund economy — its iron gates rusting, face crumbling, and garden trash-filled — was to the Time editors a clear metaphor for the sorry state of modern Japanese society as a whole.

The ultimate question asked by many in the wake of the Lucie Blackman case: why did it take the disappearance of a white woman at the hands of the Japanese not only to make the cover of Time, but to cause the authorities to move on behalf of an illegally working migrant. The answer seemed have more to do with economic clout than anything else.

Or was it racism? Complaints by authorities from less-developed countries in Japan, it appeared, were just not worthy of the same attention as those from more developed, Occidental nations. Indeed, a similar phenomenon was seen with the March 2007 murder of U.K. English teacher Lucy Hawker at the hands of a Japanese martial artist, who raped and strangled her to death. He was captured by police after two-and-a-half years on the run and sentenced to life in prison. The case received national attention, but one involving the 2006 murder of a Japanese pimp by his Thai sex slave who had endured unspeakable abuse, received far less attention.

That does say something about priorities and Japan's relationship with the rest of the world.

Gosh, this takes me back. Impossible to understate how huge this case was at the time. Also feels to me that Roppongi, for whatever it had become post bubble through the late 90s, began to morph into its next iteration from the “clean up” leading up to the 2002 World Cup featuring the closing of the magic mushrooms loophole, among other things, and after through the influx of African, and primarily Nigerian, business owners (many of whom are still friends of mine) through the 00s up to the present day. Thank you for this article (and this series). Enjoyed it a lot.