The Book of Nomo - Chapter 2 - The Early Years

TOKYO — Hideo Nomo was born to a working-class family in Osaka in 1969. His father was a big, broad-shouldered fisherman turned postal worker and his mother a part-time supermarket employee.

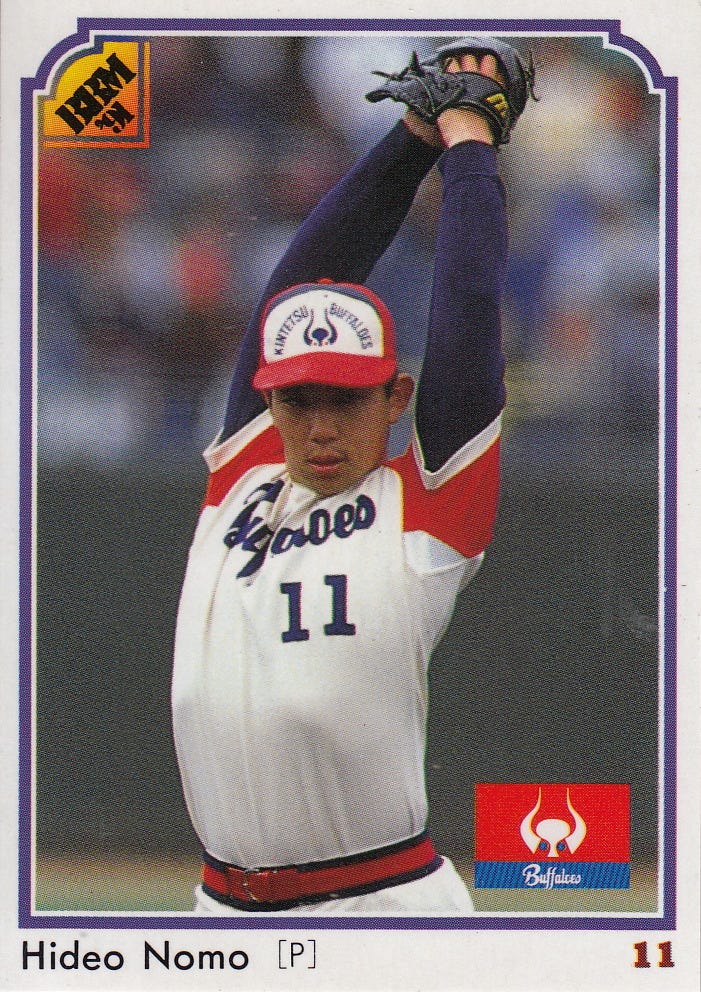

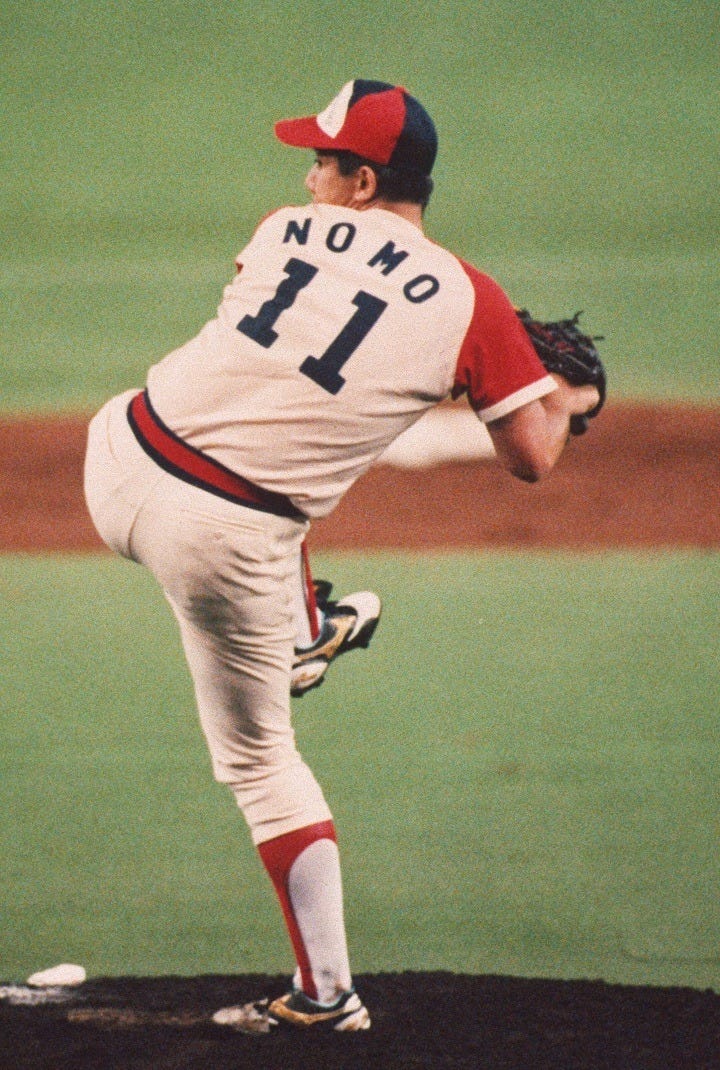

As a boy growing up, he often played catch with his father and it was to impress the senior Nomo that he developed a bizarre twisting style of throwing, so that he could get more speed on the ball. He would raise his arms high over his head, turn his back on the batter, raise his pivot leg and freeze for a second before throwing. Not only did his corkscrew form (or tornado delivery, as it was later dubbed) enable him to throw the ball harder, it also made it more difficult for the hitters to spot the ball when he delivered it.

Nomo played baseball in Little League and in middle school, but was not recruited by any of the big time high schools because of his bizarre delivery and lack of control. He spent three years at tiny, unknown Seijo Industrial High school where he grew into a strapping 6’2” 200 pounder (who was as big, if not bigger than most MLB pitchers) and developed one of the best fastballs in Japan.

But this time he was rejected by NPB scouts because of his chronic wildness (although he did pitch a perfect game in 1985 in a qualifying round for the high school summer tournament.) In 1988, he joined an Industrial League team, Shin-Nitetsu Sakai, where he learned to throw his now famous forkball. Nomo already had extraordinarily large hands. But to further develop his grip, he slept each night with a tennis ball wedged in between his first two fingers and stabilized with masking tape. His mastery of the forkball, combined with the blazing speed on his fastball and improved control, elevated him to the next level as a pitcher. Now the pro scouts were paying serious attention.

Nomo pitched on the silver medal winning Japanese baseball team in the 1988 Seoul Olympics, and was drafted by the Kintetsu Buffaloes in 1989, who offered him a then-record bonus of 100 million yen. Nomo gave the Buffaloes advance warning that he would not be easy to control when he declared that he would only agree to sign a contract with Kintetsu, if the Buffaloes coaches agreed not to change his unorthodox form. Few rookie pitchers in Japan were presumptuous enough to make that kind of demand, but Nomo was fortunate in that the manager of the team was the easy-going bon vivant Akira Ogi, a man who had elevated bar hopping to an art and knew as much about dense thicket of Minami bars as he did about the game of baseball. Ogi said, “You can do whatever way you want, as long as you win.”

Nomo debuted in 1990 and was an immediate success, going 18–8 and striking out an eye-popping total of 287 hitters in just 235 innings, including 17 in one game. He won the Rookie of the Year award, the MVP and the Sawamura Award all in one fell swoop. And he was just getting started. In his next three seasons, Nomo was as consistently good as any pitcher in all of Japanese baseball winning 17, 18 and 17 games, respectively, and leading the Pacific League in shutouts victories and strikeouts. His only weakness was control of his forkball which was unpredictable for hitters and catchers alike and resulted in a high number of walks, over 100 a year for each of his first four seasons. But it was not enough to cause him serious problems. Indeed, when Cal Ripken Jr. saw Nomo pitch in 1990, in a series of postseason exhibition games between MLB and NPB stars, he said flatly that Nomo belonged in the major leagues and would be a star there.

Nomo was a naturally shy, taciturn youth, who hid his emotions. He spent a minimum of energy communicating with his teammates and did not like talking to reporters. The more he avoided Japan’s hyperactive sports press, the more they pursued him, naturally, and that only served to intensify Nomo’s distaste for the journalistic profession. But his independent, rebellious streak revealed itself more and more as his career progressed. For example, Nomo defied a Pacific League mandate that all players wear only Mizuno shoes in the midseason All-Star series of games and signed a contract to wear the Nike brand instead. Executives in the Buffaloes office, which was getting a percentage of the P.L. deal with Mizuno, were extremely displeased. Ogi served as a buffer between Nomo, the press and the front office. But when a new manager, Keiishi Suzuki, replaced Ogi as manager in 1993, the stage was set for even more trouble.

Suzuki was one of the greatest pitchers in the history of the NPB, a barrel-chested, left-hander who had his own world class forkball and fastball, which he had used to win 317 games in a 20-year career ending in 1985, the fourth-highest total on the all-time wins list. He also had a lifetime total of 71 shutouts and 3,061 strikeouts and boasted a record that Nomo could only fantasize about: 340 games without having walked anyone, which was about 340 more walk-less games than Nomo had ever pitched. In one game in 1992, Nomo walked or hit 14 batters in four and two-thirds innings, which had to be some kind of record.

Suzuki’s philosophy of baseball was “old school” and was briefly summed up in the words “pitch until you die,” and it was diametrically opposed to that of Nomo. Whereas Suzuki had frequently pitched on two days rest throughout his career and did not mind pitching in relief on the day after throwing nine innings. On days he didn’t pitch, he went to the bullpen to practice throwing, to keep his arm strong and to hone his razor sharp control.

Nomo, on the other hand, was a student of the Nolan Ryan school of pitching and conditioning, which emphasized the more rational American system of abundant rest and weight training. Ryan of course was one of the greatest pitchers ever. He was the MLB all-time strikeout king, with a total of 5,712 strikeouts. He also had a lifetime total of 324 wins, against 292 losses and an ERA of 3.19. He pitched until he was 46 years old (several years longer than Suzuki). If you were going to copy someone, it might as well be him, Nomo did not mind throwing a lot of pitches in a game — he would throw games in which his pitch count exceeded 140 or more 61 times in his pro career — and neither did Nolan Ryan.

Like Nomo, he walked a lot of batters and once pitched a 12-inning complete game in which he threw a total of 259 pitches. But Ryan believed that 125 pitches was about the right upper limit for one game and his believed that the proper routine between starts was one of three to four days of rest combined with light throwing. He believed this was necessary so that the muscle tissue that would tear over a nine-inning effort could heal. Ryan also believed the time between starts should be filled with lots of strength training, using weights to get better balance and strength in the legs and to increase arm strength and flexibility.

Ogi had allowed Nomo to pitch and train using the Ryan way, but Suzuki found it strange. He thought throwing 100 pitches every day in practice about right and pushed Nomo to do more, on the sidelines and during games.

Nomo’s opening day performance in 1994, versus the Seibu Lions in Tokorozawa, was one of the most memorable games he would ever pitch. Nomo struck out 11 batters in the first four innings and took a no-hitter into the ninth inning, leading 1-0. With one out in the top of the inning, Buffaloes batter, Hiroo Ishii, connected for a three-run homer off starter Lions starter Kuo Tai-yuan, making the score 4-0. Nomo was within three outs of a no hitter.

However, the Lions quickly responded in the bottom of the ninth with a leadoff double and Nomo proceeded to walk the next batter. Things only became worse when the Buffaloes second baseman committed an error on a potential double play ball. With the bases loaded and no outs, Tsutomu Ito, the only Lions player whom Nomo had not struck out in the game, came to the plate. Suzuki pulled Nomo from the game and brought in reliever Motoyuki Akahori, but Ito drilled the ball into the left field stands for a sayonara grand slam. The game is considered by some to be the most devastating loss of Nomo’s career and Suzuki thought Nomo could have been mentally and physically tougher in closing it out.

Suzuki pushed Nomo to work harder in practice. He refused to remove Nomo from games where Nomo’s control was no good, as a means of toughening him up. In July of that year, for example, Nomo pitched against the Lions at Seibu Stadium and struggled with his control, walking batter after batter in the early going. But Suzuki left Nomo in the game for the full nine innings. Nomo wound up walking 16 and throwing a 191 pitches. In a previous game, Suzuki had made Nomo throw 180 pitches. By not putting a relief pitcher in on such occasions, Suzuki was trying to build what he believed was the mental toughness Nomo lacked — as well as, perhaps, put the rebellious youngster in his place. Said the American Lee Stevens, who played on Kintetsu that year, “it was clear to me that Suzuki was trying to teach Nomo some kind of lesson.”

By then, mid-1994, however, Nomo’s right pitching shoulder was giving him a lot of pain and Suzuki dispatched him to the farm team to get back in shape. To Suzuki’s way of thinking, this meant more pitching. “The best way to cure a sore arm is to throw more,” he would say, “pitch through the pain.” But this Nomo refused to do. That wasn’t in the Ryan playbook. And so Suzuki blasted him as being lazy. To placate his manager, Nomo threw in a few farm team games, but the shoulder pain only worsened. Indeed, for a time his shoulder hurt so much he had to drive his car with his left hand.

Nomo had long wanted to play in MLB, he had ever since the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when he saw Jim Abbott, the pitcher born without a right hand, and other Americans playing for Team USA. He watched them play and said to himself that he was just as good as any pitcher the Americans had to offer. This conviction was strengthened by Nomo’s success in post-season matchups against visiting MLB All-Star teams when he faced superstars like Cal Ripken Jr. and Barry Bonds. He came to believe that he could throw a baseball as well as anybody else in he world.

While pitching for Kintetsu, the MLB was not far from Nomo’s mind. He kept baseball cards of favored American players in the MLB taped to his locker door in Fujiidera Stadium, and talked to his gaijin teammates about life in major leagues. He waited and hoped that an opportunity would present itself — before he had pitched the 10 years required for free agency, under the system established in 1992, or his arm disintegrated.

In 1994, a player agent named Don Nomura offered him a way out. Nomura was a half-Japanese, half-Caucasian, a six-footer in his mid-30s who had been raised in Japan and had only recently become an agent, after a varied career that included playing for the Yakult Swallows farm team, making a fortune in real estate in Southern California, and owning the Salinas Spurs minor league baseball team. Nomura had been looking for a Japanese player who wanted to try his hand in the MLB, someone restless enough, talented enough and courageous enough to want to challenge the system. And Nomo fit the bill.

Nomura had studied the Japanese Uniform Players Contract intensively for loopholes. He had it translated and had enlisted legal help in the U.S. to see if anyone could find a way whereby a Japanese player could obtain his freedom. A friend of his, an agent based in Southern California named Arn Tellem (who would years later represent Hideki Matsui), studied the contract and discovered something that might do the trick: the “voluntary retirement” clause.

The Japanese UPC was basically the same as the MLB player contract, with one fundamental difference that had not been noticed by anyone else. In the MLB pact, a voluntarily retired player who wished to return to active status could play only with his former team (unless, that is, he had become eligible for free agency). In Japan, a player who voluntarily retired was obligated to return to his former team as long as he stayed in Japan. Going to the U.S. to play was an entirely different matter it seemed. Under the rules as they were written, a player who went on the voluntarily retired list in NPB would thus essentially be free to play in the U.S.

The MLB and Japan baseball commissioner were still bound by the U.S.-Japan Player Contract Agreement, also known as the Working Agreement which had been drafted and signed in the wake of the Masanori Murakami affair. For those who don’t know the story, Murakami had been drafted and signed by the Nankai Hawks as a 19-year old and sent directly to train in the San Francisco Giants minor league system, in 1964, as part of a player training and exchange program the two clubs had arranged with each other. Murakami had expected he would put in his two years at the Giants Class A minor league franchise in Fresno or some such place. But, to the surprise of everyone on both sides of the Pacific, he was suddenly called up to the Giants at the end of the year. He did so well — an ERA of 1.80 in 15 innings pitched — that the Giants were delighted and offered him a contract. Murakami signed without hesitation (and no doubt without knowing what he was doing), because he was now contractually obligated to two different teams, one in Japan and one in the U.S.

A long, bitter tug-of-war ensued that threatened to ruin U.S.-Japan baseball relations. In the end, a compromise was reached whereby Murakami would pitch one more year in San Francisco, then return to Japan permanently to play for the Hawks. The two countries would then sign an agreement to keep their hands off of each other’s players without explicit permission from the teams involved. The Working Agreement obligated both sides to abide by the rules as specified in the respective baseball contracts and conventions.

However, the discovery that the standard UPC in Japan failed to specify worldwide rights in regard to the ownership of players, inadvertent though that failure to specify may have been, provided the U.S. side with an opening to go after Japan’s stars, without actually violating any of the conditions of the Working Agreement.

The UPC omission was perhaps understandable given the big gap that was believed to exist between the levels of play in the two countries at the time the document was signed — not to mention the social taboos that existed at the time which required Japanese players to be loyal to Japan.

In the late 60’s and early 70’s, owners of the Dodgers and White Sox had, actually, approached Yomiuri about acquiring the service of Kyojin stars Shigeo Nagashima and Sadaharu Oh, but in both cases Yomiuri owner Matsutaro Shoriki had said no. Not that either star would have gone anyway given the strong nationalistic mood at the time. But, as Oh had put it, “I really wanted to go and test my abilities in MLB, but even if I had been allowed to go by Yomiuri, the fans never would have forgiven me. That was the mentality of the time.”

The existence of the voluntary retired clause was confirmed and clarified in a series of back-to-back letters sent back and forth between the U.S. and Japan — the exchange having been prompted by Don Nomura. The key document was a fax sent by Yoshiaki Kanai, the executive secretary to the Japanese baseball commissioner, on Dec. 9, 1994. It was a letter in response to faxes from William A. Murray, the executive of baseball operations in the MLB Commissioner’s Office in New York, inquiring about the eligibility of voluntarily retired players moving abroad.

The key passage in the final faxed reply sent by Kanai went as follows: “If a voluntarily retired player in Japan wishes to return to active status, he may sign only with his former team as far as he chooses to do so within our country, in other words he would be able to contact with teams in the United States.”

That was as concrete as one could possibly make it. Although Kanai, a former sportswriter, surely never intended his letter as an instrument by which Japanese stars could gain their freedom, that it is exactly what it became.

Nomo made a pretext of negotiating with Kintetsu officials in the off-season sessions to discuss his contract. His annual salary at the time was $1.5 million and he asked for a three-year, $9 million contract. The front office, as Nomo had expected, turned him down flat. He was too young for that kind of deal, they said, besides he had had a bad year and a sore arm to boot. No way.

Nomo said fine, I understand. Then he declared his voluntary retirement from Japanese baseball.

At first, the Kintetsu executives involved, unaware of the existence of the Kanai-Murray letters, were incredulous. They did not believe Nomo.

“This is crazy,” exclaimed one official, “Think of what you are doing to your career.”

“I am,” said Nomo, “That’s why I am leaving.”

A few days later, he signed a letter of retirement and walked out of the Kintetsu offices a free man.

Kinetsu had lost their best player before they even realized what was going on. When word got out in succeeding days that Nomo, and Nomura, were putting out feelers to West Coast MLB teams, Kintetsu appealed to the NPB Commissioner’s office for help. But nothing could be done. The commissioner’s office was just as perplexed. They had automatically assumed that the Murray query was about “gaijin” players in Japan, not Japanese, since the idea of a Japanese star in the prime of his years going to the States was still about as remote as the Japanese landing a man on the Moon, and when they realized what had happened, they were not happy.

“The MLB tricked us,” said one official, “we won’t forget this.” shortly thereafter, Nomura gave a press conference at the FCCJ, in which he held up copies of the Kanai-Murray letters for a room packed with foreign journalists to see. The authenticity of the letters could not be disputed, and their meaning was clear.

Kintetsu, embarrassed, had no choice but to go into face-saving mode.

“Do you want our permission to let you go to the States,” one official asked as a subsequent meeting, “We can arrange to do that.”

But Nomo was merciless.

“I don’t need your permission to go to the States and play,” said Nomo.

And he didn’t.

All Kintetsu could do was announce that they were releasing Nomo, with the blessing of the NPB commissioner, so that he could pursue an MLB career.

The barrage of criticism and insults that Nomo faced over the next few weeks, was intense. Nomo was labeled an “ingrate,” a “troublemaker,” a “traitor.” Everyone had turned against him, the sports papers, baseball officials, fan groups and even big names like Oh, Nagashima and Senichi Hoshino.

Among his critics was Nomo’s own father. “You don’t have to embarrass the folks at Kintetsu like this,” he said, ” If you want to go, you have to find a better way.”

“There is no better way,” said Nomo, “and I don’t want to spent the rest of my life regretting that I never tried. I want to see if I have what it takes to make it in the MLB.”

It took an enormous amount of courage to do what Nomo did. The pressure grew so intense that even Nomura, his agent, began to have doubts about what they were doing and whether it was the right course of action.

But Nomo never wavered. Not once.

“Don’t worry,” he would say, “We are doing the right thing.”