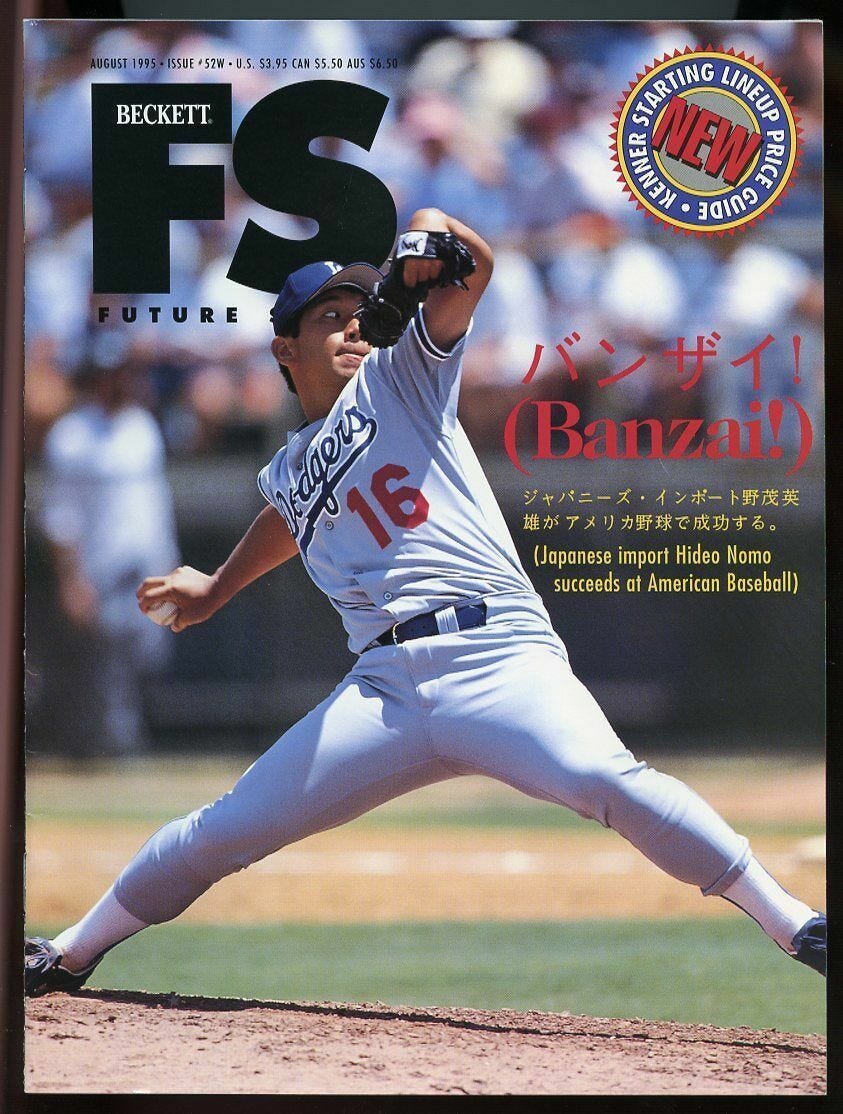

TOKYO — There are many observers who would say that Nomo was the most dominating pitcher in the MLB in his first two years, as well as perhaps it hardest worker. He set an MLB record by compiling 500 strikeouts in his first 445 innings and finished fourth in the Cy Young balloting in 1996.

However, he began to slip in 1997 when he compiled a 14-12 record and his ERA ballooned to 4.25. During the subsequent offseason he underwent surgery for bone chips in his elbow (the result off a line drive off the bat of Philadelphia Phillies slugger Scott Rolen), but his performance continued to decline. He slipped to a mark of 2-7 in the first half of the 1998 season and for the first time in Nomo’s MLB career, one could actually hear boos in some games he pitched at Chavez Ravine. By mid-season, both Nomo and the Dodgers, now under new ownership, had had enough of each other, and Nomo was dispatched to the New York Mets, where his decline continued.

After three full years, the Nomo Effect on MLB was clearly visible. He had made his presence felt in a number of ways, not the least of which was in the inflated income of his teammate and catcher Mike Piazza. Nomo had become such a fixture on NHK that, as one cynic, Bobby Valentine, who had managed in Japan in 1995, cracked, “You could not only see him on TV on the day he pitched, but also the day before and the day after.” It also meant that NHK viewers could see Nomo’s catcher, Mike Piazza, The tall strapping mustachioed Piazza, became such a celebrity in Japan, thanks to his NHK exposure, he garnered a series of lucrative endorsement deals, including Gunze underwear, Komatsu construction equipment and Mizuno bats. Piazza appeared in numerous TV ads, magazines and newspapers in Japan pushing these products, and, in fact, during the offseason, he made annual trips to Tokyo to look after his endorsement interests. In December 1996, after the completion of Nomo’s second year in MLB, Piazza visited Japan on a 10-day trip and was hounded by the media. During that trip, Piazza was invited to play in a golf tournament with Tiger Woods. The fact that on one hole, Piazza’s drive traveled farther than that of Woods, was cause for huge headlines in the sports papers the next day.

It was estimated that Piazza made anywhere from $3 million to $6 million a year for his endorsements in Japan. Since the Dodgers paid Piazza $7 million a year for his services as a baseball catcher, this meant that Piazza nearly matched his MLB salary in income from Japan.

What American observers found curious, however, was that Piazza’s celebrity in Japan had little to do with his stature as a perennial All-Star catcher in MLB. Piazza was, in fact, one of the greatest hitting catchers in the history of the game, hitting 427 homers in a 17-year career. During Nomo’s first three years in L.A., Piazza hit 32, 36 and 40 homes, respectively, helping Nomo win many games and pulling in, in his own right, millions of dollars in endorsement money in the U.S. from companies Pert Plus shampoo and Nike. But all that seemed to matter in Japan was that he was Nomo’s catcher.

The beginning of the end for the Nomo-Piazza team came in 1998 when Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News megacorporation/Fox Entertainment Group bought the Dodgers in 1998, for $350 million, the most expensive franchise purchase in the history of MLB. The sale of the Dodgers was attributed to the changing economics of the game, escalating player salaries and the risk of labor disputes and walkouts. Dodgers President and owner Peter O’Malley had said before the sale that a family-run company could no longer afford to run an MLB club and arranged for Fox to buy the team. O’Malley accepted a marginal position as advisor during the transition from one owner to another. Dodgers manager Tom Lasorda resigned, (Lasorda had already resigned in June 1996, because of health reasons, replaced by Bill Russell well before Fox Entertainment bought team in March 1998) ). Then in the spring of 1998, the new owners unloaded Piazza to the Florida Marlins, who in turn traded him to the Mets.

Nomo was unhappy at these changes. He had been unusually close to O'Malley, whose family had helped spur baseball's growth in the Pacific Rim, and was displeased at the reduced role O’Malley was given by the team’s new ownership. He was also unhappy that Lasorda and pitching coach Dave Wallace, with whom he was close as well, had left and that the only catcher he had known in Los Angeles, Piazza, was also gone. when a rumor circulated that the Dodgers were planning to ship Nomo to Seattle, that was the last straw. Nomo and his agent, Don Nomura, demanded a trade.

The rumor had been false. but with Nomo’s win record at 2-7 and ERA of 5.05 in mid-year and hitters learning to lay off Nomo’s forkball, which he threw inconsistently for strikes, general manager Fred Claire was happy to give Nomo what he'd asked for, designating him for assignment, then trading him to the Mets.

However, Nomo’s reunion with Piazza was brief and unmemorable. By then, Nomo, had also lost his fastball and National League batters had gotten used to his bizarre pitching motion. He won but four more games in New York, lost five with an ERA of 4.82 and the Mets front office would see fit to release him.

Piazza, for his part, would stay in New York for eight years, enjoy many All-Star level seasons and lead the Mets to the World Series in 2000. But since he was no longer known as Nomo’s catcher, his endorsements dried up — except for a brief period of time when he became known as Masato Yoshii’s catcher.

Some social scientists in America thought the experience of Piazza vis a vis Nomo said something about the Japanese national character — something that was not entirely positive. MIT professor David Friedman, a New York Times contributor and frequent critic of Japan, called it “yet another example of Japanese provincialism at work.” While Fred Notehelfer, director of the Center for Japanese Studies at UCLA, simply explained it to the Los Angeles media, that the phenomenon was simply one of the curious things about the Japanese people.

“The Japanese are loyal to Nomo,” he said, “They’re loyal to things Japanese. They’re not loyal to much else. Period.”

OPEN GATES

The Nomo effect extended into other areas as well. Since Nomo had been such a roaring success, everyone in the MLB was looking for the next big star from Japan and since the agent Don Nomura had been the one who had brought Nomo to North America, everyone looked to Nomura to bring him in.

Nomura was truly a bilingual, bicultural individual. The son of an American civilian who had worked in Japan during the Occupation and a Japanese woman (the infamous Sachi who divorced his father and eventually married Katsuya Nomura), he was raised in Japan and college-educated in the U.S. A high school baseball standout, he played briefly for the Yakult Swallows for a time during the 70’s, mostly on their farm team, then went into business in Los Angeles. He had earned enough money playing baccarat in Las Vegas to go into the real estate business, rode the stock market and real estate booms of the late 80’s, then purchased an interest in the minor league Salinas Spurs. Having had worked briefly with baseball scout Ray Poitevint, Nomura decided to become a full-time agent after successfully signing and marketing his first client — a clubhouse boy on the Spurs from Japan, Mac Suzuki.

Nomura was convinced there were any number of players in Japan who could play in the MLB and even become stars. They were held back by the old idea prevalent in the MLB that the Japanese were not really good enough to play in the leagues, as well as an unwillingness on the part of the players to challenge the system, and a reserve clause which bound a player to his Japanese team as long as the team wanted. That clause had been modified in 1992 to accommodate a 10-year free agent system instituted by NPB owners (meaning the two most powerful owners Yomiuri’s Tsuneo Watanabe and Seibu’s Yoshiaki Tsutsumi), that was based on a belief that the free-agent player would head for Kyojin or Seibu, and never be so bold as to try to go to the MLB.

By the 90’s however, the attitude of Japanese players was not quite as submissive as it had once been. Players were more sophisticated about the major leagues, thanks to advances in jet travel, satellite TV, and the advent of the Internet. Enter Nomo, bristling about being treated like chattel by his Kintetsu Buffaloes masters. When he combined forces with the half-Japanese and half-American Nomura, a man who was simmering with resentment at the various discriminations he had endured growing up as a schoolboy in Tokyo, the right team to challenge the system head on had been formed.

Although Nomura had been the instigator, it was Nomo who often held them together. During the brouhaha with Kintetsu that followed in the wake of Nomo’s voluntary retirement, both men had been bombarded with threatening telephone calls and postcards. “You’re greedy, and a cheater,” and “Get the hell out of Japan,” were among the more common messages. Yomiuri owner Watanabe publicly branded him Nomo and Nomura, “bad people.”

But whenever Nomura expressed concern, Nomo just shrugged and said, “let them talk. It’s just hot air.”

Nomura’s next project was Hideki Irabu, a burly , 6’4” 220 pound, young man who could throw the ball at 99 miles per hour, a Japan record, and who, by the age of 27 had taken Nomo’s place as the premier strikeout pitcher in Japan. Irabu, himself of mixed-blood origins (he was the son of a unknown GI and a Japanese mother from Okinawa) — was eager to follow in Nomo’s footsteps and defy the system. He played for Valentine at Lotte in 1995, a year when he led the Pacific League in ERA and strikeouts, and thought the bushido philosophy of GM Tatsuro Hirooka was outdated.

Irabu hired Nomura, but instead of opting for the voluntary retired clause that had given Nomo his freedom, he took Nomura’s advice and adopted a different strategy, requesting a trade to the New York Yankees. Lotte obliged by trading him to the San Diego Padres, but Irabu refused to sign a contract with that team. Another complicated international brouhaha erupted, in which Nomura and Irabu claimed that Lotte and San Diego were engaging in a “slave trade.” Nomura even compared the treatment of Irabu to that of Japanese-Americans who had been put in concentration camps in the U.S. during World War II.

However over the top that might have been, some observers did see racism in the way Irabu was treated. Gene Orza, attorney for the MLBPA said, “None of this would have happened if Irabu were an American with blond hair and blue eyes. They would not trade a player in that manner. Lotte and San Diego did without first asking his permission. But because he is Japanese, MLB teams think they can treat him like dirt.”

The matter went to the executive council. In the end, the MLB executive council ruled that the trade would have to stand, but did, nonetheless, put a freeze on future such transactions unless there was unanimous consent by all parties. Nomura and Irabu still refused to sign and eventually a deal was worked out allowing Irabu to sign with New York.

Once a Yankee, Irabu almost singlehandedly undid all the good will Nomo had created. Irabu hated reporters, Japanese reporters, that is, even more than Nomo. Also, unlike Nomo, Irabu had a mean streak. He took to insulting the writers who were assigned to follow him during his preparatory training sessions in Columbus, Ohio. He sneeringly called them “goldfish shit” and “grasshoppers/locusts.” During one practice, he whacked a reporter in thigh with a fastball. Irabu claimed it was an accident, but just about everyone else thought it had been intentional.

Called up to the Yankees, Irabu had streaks of very good pitching and streaks of very bad pitching. He won 13 games in 1998 and was the first player in the history of the MLB to win the Pitcher of the Month award twice in one season. Yankees pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre was so impressed that he said, “When Hideki is on, he has the best stuff of anyone I have ever seen anywhere. “

The problem was Irabu was only on half the time. The other half, a switch turned inside his head, and he was abominable. His control and his fastball disappeared and he looked like a high school pitcher. In one game versus Oakland, Irabu could not hold a 10-0 lead given to him in the early innings, sending Yankee manager Joe Torre into a fit of anger.

Irabu also lacked Nomo’s self-control and was guilty of several adolescent outbursts during his time with the Yankees. He stomped his feet in anger on the mound, glared at umpires, threw his glove on the ground. In Milwaukee one time, he spat in the direction of booing fans. He punched a hole in a clubhouse door at Yankee Stadium. One New York writer called him a big baby. Another chided him for his smoking and drinking and for coming under the influence of Yankees lefthander David Wells, a rabble rouser who would claim, infamously that he was half drunk and half hungover while he pitched a perfect game. Irabu’s weight ballooned while with the Yankees, prompting owner George Steinbrenner to call him “a fat, pussy toad.” During games he wasn’t pitching, he took to sitting off by himself, in the bullpen, away from the fans and his teammates. Don Nomura’s opinionated mother Satchi labeled him “the shame of Japan.”

Some people said that the problem was that Irabu had never known his father and was suffering an identity crisis. He had been raised by an Osaka restaurateur who had married Irabu’s mother, and refused to answer any questions about his background. Others said he suffered from a chemical imbalance and needed to see a psychiatrist. Whatever the reason, the Yankees eventually gave up on him and shipped him off to Montreal, who in turn shipped him to Texas, who then released him so he could come back to Japan and pitch for the Hanshin Tigers.

YOSHII

Don Nomura’s next client in MLB, with the timely help of Hideo Nomo, was Masato Yoshii who he signed with the New York Mets after completing his 10-year service requirement and declaring free agency. Yoshii and Irabu were as far away in personality — not to mention baseball ability — as one could imagine. The only thing they had in common perhaps was that they were both from Japan, were both pitchers, and, like Nomo, were both big, with broad shoulders and big legs. Yoshii was 6’ 2” and weighed 210 pounds. In fact, both Nomo, Irabu and Yoshii were taller than the average MLB player, who stood at just six feet.

But that was where the differences ended. Irabu threw hard, Yoshii did not. Irabu was noted for his childish behavior, Yoshii for his composure and poise. Whereas, Irabu bullied the San Diego Padres into trading his rights. Yoshii was the model of good manners. In fact, when Yoshii became a free agent in Japan, after 10 years with the Yakult Swallows and after leading them to the 1997 Japan Series championship, with a record of 13-6 and an ERA of 2.99, he initially felt obligated to stay with them and take the two-year contract they had offered.

“I owe them,” he had told Nomura, when the agent approached him about going to the MLB.

“What you owe,” said Nomura “is to your fellow players. You have rights. You make a stand for the next generation.”

Yoshii eventually declared free agency, after much emotional angst, and after apologizing to Yakult and Swallows manager Katsuya Nomura for his selfish behavior. Many teams offered him lucrative contracts, led by the Yomiuri Giants who dangled a $9 million deal over four years.

The Giants refused to meet with Nomura, maintaining a policy of not negotiating with player agents. So Yoshii memorized a set of instructions from Nomura and met with Giants manager Shigeo Nagashima, his boyhood idol. He told him that he wanted an extra $4 million and the right to choose his own training routine, which meant no more 100 pitch-a-day sessions in camp. When dictatorial Yomiuri owner Watanabe heard this he was apoplectic. Take the deal or get the hell out, he said.

Yoshii, not wishing to offend, was about to bend to the Yomiuri wishes, when he got a phone call that would change his mind. It was from Nomo, who told him that the most important thing in life was “following your heart.”

“If you stay in Japan, Masato,” he said, “and sign with the Giants or some other team, you would regret it the rest of his life.”

“Stop and think what you’re doing,” said Nomo, “Get a hold of yourself.”

Yoshii, stopped, thought, got a hold of himself and then did one of the most amazing things a Japanese ballplayer, or any ballplayer, for that matter, has ever done. He turned down the millions of dollars that Kyojin had offered him and then accepted a deal from the New York Mets, a one-year pact for only $200,000. Any other money he would get would be from performance bonuses. It was a remarkable display of courage.

Fortunately, Yoshii would pitch for Valentine, who had seen Yoshii in Japan three years earlier and thought highly of him. Valentine stuck him in the starting rotation and Yoshii finished that 1998 campaign with record of 6-8 in 29 games and an ERA of 3.98. The Mets rewarded him with a two-year deal for $5.25 million. Yoshii was 12-8 next year and led the Mets into the playoffs, compiling an ERA of 1.98 for the important stretch month of September with five wins. Valentine told reporters, “Yoshii is our most reliable starter.”

Nomo should have gotten a commission from the Mets for bringing Yoshii in.

HASEGAWA

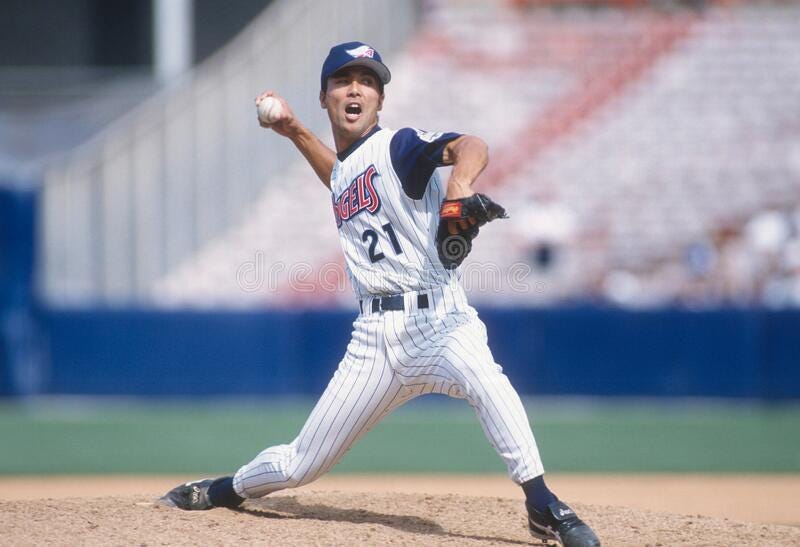

Another notable who followed in Nomo’s footsteps to MLB was Shigetoshi Hasegawa. Hasegawa had been a solid, if unspectacular pitcher with the Orix BlueWave. At only 5’ 9” and 170 pounds, he was considerably smaller than Nomo, but he carved out a fairly successful career by using breaking pitches, including a forkball, a slider, and a changeup he had learned from American pitching coach Jim Colborn, who was with Orix from 1990 to 1994. After compiling a poor 4-6 5.43 record in 1996, the BlueWave lost interest and agreed to let him go to the MLB, even though he was four years away from free agency. They dealt him to the Anaheim Angels, who paid Orix $1 million, and $350,000 directly to Hasegawa to sign. Interestingly, Hasegawa opted not to enlist the services of Don Nomura, whose reputation had taken a beating in Japan in the wake of the bad publicity surrounding both Nomo and Irabu deals. Instead he went with a veteran American agent named Ed Kleven, who represented mainly people who worked in the media.

In the beginning, Angels manager Terry Collins was not particularly impressed with Hasegawa. “He certainly doesn’t compare to Hideo Nomo,” said Collins in an interview, shortly after he assigned Hasegawa to the bullpen.

But Hasegawa steadily improved, with help from his teammates. “His first year, he kept pitching down-and-in to left-handed hitters, because it's a good pitch in Japan,'' Angels pitching star Troy Percival said. “I asked him about it and he said, ‘Down and in . . .good pitch.’ I said, ‘No, lefties here kill that pitch.’ ”

Hasegawa listened to Percival’s advice and adjusted his approach accordingly. By the end of the season, Hasegawa had turned himself into a reliable setup man. He went 3-7, with a 3.93 ERA and pitched in 116 innings, making many necessary adjustments in the process. In his second year, he had lowered his ERA to 3.14.

On top of that, Hasegawa, had hit the weights hard, something Japanese players at the time did not necessarily believe in as strongly as players in the MLB. The result was an increase in velocity on his fastball from about 87 mph to 91.

People said that Hasegawa’s biggest strength, as least as compared to Irabu was, his willingness to adjust. Moreover, unlike Nomo, or Irabu, he loved learning English. He studied English texts, read books like Das Kapital, and welcomed the chance to speak English in live interviews. He was said to be the only MLB player to read the Wall Street Journal in the locker room or talk stocks and bonds with teammates in pre-game practice. Unlike Nomo, who could not wait to get out of the clubhouse, Hasegawa could not wait for a chance to practice his English with American reporters. He often said that he did not move to the U.S.. to play in MLB, rather he entered the MLB because he wanted to live in the U.S. indeed, after he retired from his 9-year MLB career — during which time he would make one All-Star team as a reliever (2003) and go on to gain the record for most appearances by an Asian pitcher in MLB ahead of Nomo, he would remain in the U.S. and become a real estate agent in Newport Beach, California.

Hasegawa also had a sense of humor, another thing that separated him from Nomo and Irabu. In his first season, the movie “Midway” was being shown in the Angels clubhouse one day after Nomo and the Dodgers had beaten the Angels. During the movie — about one of the World War II battles between the U.S. and Japan — one Angel yelled at Hasegawa, “How about that, Shige?” as U.S. planes bombed a Japanese ship

Hasegawa replied, in English, to a roar of laughter, “Too bad you couldn’t do that to Nomo.”

As the 20th century drew to a close, Japanese players had become an important part of a growing trend toward internationalization in the MLB. The MLB was suffering competition from other sports like the NFL and the NBA. Professional baseball was no longer America’s national sport and many of the country’s best athletes went into other sports, which offered more money up front, and did not require years of servitude in the minor leagues.

However, MLB revenue had increased, thanks to a new system of integrated TV and other media rights instituted and controlled by the commissioner’s office, as well as a trend, begun in the early 90’s of having cities build new stadiums for their MLB teams.

The money MLB teams saved from having free ballparks alone was put to good use to deal with the player shortage problem, buying up players from other countries, such as Japan, Korea and Latin America. By the year 2000, over a quarter of the players in MLB came from foreign countries, and well over 40% of the players in the minor leagues had passports from other countries. In the decade since Nomo first arrived, nearly two dozen Japanese players would don the uniform of a major league team, and those players, in turn, would attract Japanese fans to the ballpark, much as Nomo attracted fans to Los Angeles and New York, be they from the immediate area, or be they “baseball tourists” all the way from Japan. They would help change the economic landscape of Major League Baseball.

By this time, there was also enough cumulative experience among Japanese players to make a judgement as to whether or not playing in MLB was worthwhile. The benefits of playing Major League Baseball were obvious to Japanese who were there. They found several reasons to remain in the North America, beginning with the new validation of self-worth and the benefits of the looser, freer major league system, where for the first time they had a real say in determining their practice routines as well as in negotiating their salaries. As Nomo put it, “It's a great feeling to be responsible for yourself and to be free to be yourself. In Japan, you're treated like a child.”

Then there were the ballparks with natural grass, and the unrestrained expressiveness of U.S. fans, even those in New York. As Yoshii put it, “In the U.S. they are easy to understand. When you play well, they give you a big round of applause. When you do bad, they boo you. In Tokyo always the same: trumpets, whistles and chanting in the oendan [cheering section]. Silence in the rest of the stands."

Of course, money was also a factor. Although many players did accept less money to emigrate to America in the beginning, they stood to pocket more lucre in the long run, given the major league salary structure and the potential for increased commercial endorsements not only in North America, but also at home, where many players became more popular than ever because of their major league cachet.

On the other hand, this is not to say that playing in North America was an unending experience of unalloyed joy for Japanese besuboru migrant. While most Japanese players appreciated the less regimented MLB baseball culture, they also thought that it helped to create “unfinished” athletes, players who were less skilled in the fundamentals and the finer points of the game — such as the bunt, the hit-and-run, hitting to the opposite field, baserunning, defensive relays — because they did not practice them endlessly from Little League on up the way up like young players in Japan did. The constant emphasis on power, they believed, was a detriment to equally important parts of the game, such as advancing the runner.

More over there were a myriad of tiny adjustments they found it necessary to make. Japanese looked askance at such long-standing American baseball customs as chewing tobacco and spitting it on the dugout floor — “disgusting” is how cleanliness-conscious Japanese players commonly described it. They found confusing the myriad unwritten rules of behavior that major leaguers have concocted to protect their all-important pride: No bunting or stealing with a big lead was one; no crowd-pleasing fist in the air (gattsu pozu) is another. The Japanese could not understand why such conduct was viewed in the majors as “showing up the opposition” and an invitation to reprisal in the form of a fastball to the ribs, when players get away with similar behavior in the NFL and the NBA? Then there was the puerile tendency of big leaguers to play practical jokes, like putting itching powder in a teammate's talcum container. This was simply not normally done in Japan where wa (group harmony) is so important.

But outside the ballpark was where adjustments were most difficult for Japanese players. Few of them spoke English well enough to carry on conversations with teammates, so it was wearying for them to spend even an evening over dinner communicating through an interpreter. Thus most Japanese players passed their free time with other expatriates or visitors from Mother Nippon, catching up on news from home and trying to figure out what makes “Americans tick.”

The Japanese players’ sense of isolation was heightened by the constant travel, the long plane rides and the countless nights in strange cities where most people had never even met a Japanese. (Kansas City was one of the least desirable destinations because it is difficult to find a decent Japanese restaurant there.) As Don Nomura described it, “You play a game that ends at 10, and then you're ready to go out, but all the good places to eat — Japanese or otherwise — are closing up,” he said. “You go back to your hotel room, order a cheeseburger from room service and turn on the TV, but you can't understand what the people are saying. It can really get to you after a while.”

Jack Howell, former MLB star, who played for Yakult and the Giants, as well as the Anaheim Angels, where he was a teammate of Hasegawa, understood the problems Japanese players were facing in their attempt to assimilate themselves into both American baseball and society. Howell played for three years in Japan, where he had to learn new customs while trying to perform under a microscope — especially under the Yomiuri microscope. Howell made it a point to try to explain to other Americans just how difficult it was to make adjustments to another culture.

“When they go home at night, they are facing another whole challenge,” Howell said "Where they eat, communicating with people, how to get around, understanding and learning the culture. The (Japanese) media follows them everywhere, especially guys like Nomo. They crouch behind cars, bushes. But both Nomo and Hasegawa have the right attitude. They try to fit in. Some Americans that went over to Japan kind of had bad attitude like, ‘I'm a big-leaguer from the real big leagues.’ The Japanese didn’t appreciate that. But from what I see of Nomo, and of Hasegawa, they are different. They try to fit in.”

Then there were the subtle and not-so-subtle discriminations that people of Asian origin sometimes face. Some Japanese players complained of hearing racially derogatory comments from the stands, if not from other ballplayers.

But on balance, the pluses outweighed the minuses, especially off the field. And for ballplayers, one of the things they liked best about North America was the vast spaciousness — in particular the roominess of the houses and the accessibility of golf courses — which compared most favorably to the cramped conditions on Japan’s crowded islands. It was why Hasegawa stayed in the U.S. during the offseason.

Howell was one of many American baseballers with experience in Japan who rated the quality of Japanese pro baseball high. He maintained that many players in Japan were of major league quality and believed that if free agency rules were modified from the 10 years at the time to six years, then there would be many more players in their prime— especially pitchers — who could play in MLB.

However, he was quick to add that it took something special — something mental, as well as physical — a special character to make it in the MLB. Some players had it. Some did not. Nomo had it in spades. Nomo’s character was “off the charts,” as Colborn, the former pitching star and MLB coach put it. Irabu’s didn’t. But Hasegawa did. And so did Yoshii.

In New York, Nomo and Yoshii had become the first Japanese teammates on an MLB team. For a time, Shea Stadium was a shining example of internationalization. In June 1998, for example, Nomo and Yoshii sang Happy Birthday in English to the daughter of the Mets Latin catcher, Albert Castillo, at the Castillo home. And Nomo could be heard translating basic English expressions for Yoshii. Nomomania was even transposed from Los Angeles to New York.

But then, Nomo began to demonstrate that he no longer had a decent fastball. And Nomo learned how quickly you could wear out your welcome in MLB once that happened, especially in a tough town like New York. By August, the long knives were out, and there were calls for his head. Said writer T.J. Quinn, who reported for a New York area paper, “Nomo takes forever to pitch a game. He walks too many batters and he relies on only two pitches, one of which is a poor excuse for a fastball … The guy can’t be sent to the bullpen, because nobody wants a relief pitcher with no control. What’s more, he is a lousy interview and he has no sense of humor. It’s time to get rid of him. Trade him for anyone. Anyone who owns a glove. Or put him on waivers and give him his unconditional release. But just get rid of him as soon as possible.”

The Mets listened to Quinn’s advice. They awarded Yoshii with a new contract at the end of 1998, two years at $5 million, and showed Nomo, with his ERA at nearly 5.00, the door.

By this time, much of Japan had lost interest in Nomo. Instead, they were paying attention to the home run race between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, telecast by NHK almost daily. McGwire hit 70 home runs, to set a new record. Sosa hit 66. It was on the most exciting home run races in the history of MLB (and was a big exception to the belief that Japanese would not watch MLB baseball if there were no Japanese players involved.) What nobody knew at the time was how much both players were using steroids.

However, the wave of internationalization started by Nomo continued to grow. This new plateau was reached in 2000 when the Mets faced the Chicago Cubs playing Opening Day in Tokyo. They were the first official MLB games ever played in Japan.

And it was only the beginning.

SASAKI

In 2000, the newest addition to the Japanese butai in the MLB, was a 6'4", 220-pound reliever, Kazuhiro Sasaki, who won five “Fireman of the Year” awards and was so imposing he was nicknamed “Daimajin” after a giant stone samurai that comes to life on celluloid to rescue imperiled villagers. Sasaki had long thought about leaving Japan for the MLB. He had been inspired by Nomo, Irabu and the others and in 2000, using agent Tony Attanasio, who would later represent Ichiro Suzuki, signed a contract with the Seattle Mariners. There he set a team record for most saves and won the Rookie of the Year, the second Japanese pitcher to win that honor after Nomo. He racked up 45 saves in his second year, 2001, (the year another Ichiro joined the Mariners) and became such a favorite that he appeared in a Mariners commercial, dressed as one of the Three Musketeers (the other two were Jeff Nelson and Arthur Rhodes).

Japanese pride was flying high. The achievements of Nomo and Sasaki, and to a lesser extent Hasegawa and Yoshii, were indeed inspiring. For those older fans who remembered the days when MLB teams like the New York Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers would visit Japan on a postseason tour and annihilate their Japanese competition, it was like a miracle.

Said Kozo Abe, a veteran reporter with the Yukan Fuji, “I remember Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle coming to Japan. I looked up at them as gods. Now we are balancing the scales. It was something we once thought was impossible.”

Great journey in the baseball time machine.