TOKYO — This is a book about Hideo Nomo, the baseball player and social icon, as I view him. It is the product of several dozen interviews with people who knew and/or played with Nomo and a lengthy search through newspaper and magazine files dating back to 1990 when I first saw Nomo pitch for the Kintetsu Buffaloes.

Although this is the first book I have done about Nomo, I have written about him in several other venues over the years. The first time was an essay for the Shukan Asahi during his fabulous rookie season in 1990 season, when I was doing a weekly column for that magazine, and Nomo was setting the baseball world afire with his tornado windup and his dramatic strikeouts. In the essay, I ranked him up there with the best pitchers in MLB at the time, including Randy Johnson. In fact, at the end of that season, I gave a speech at famed Occidental College in Los Angeles, when the trade paperback version of You Gotta Have Wa first came out, and I cited Nomo when one of the students asked me during the Q&A period after the lecture if there were any Japanese players who were capable of becoming stars in MLB. I told him Nomo’s fastball was faster than most MLB pitchers’ fastballs and that there was no one in America capable of throwing a forkball like Nomo. I remembered telling them that it was too bad that NPB rules prohibited Japanese stars from leaving Japan to play in the States, because there were other players besides who could also make an impact.

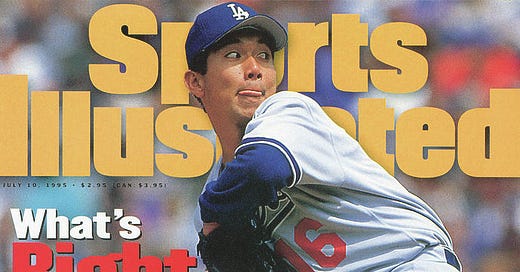

The people in the audience were polite, but they didn’t seem to really believe me, because the reputation of Japanese baseball in America at the time was very low. Indeed, I got the same reaction when I gave a similar talk to the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan in Tokyo a couple of months later. Thus I felt vindicated when four years later Nomo moved to the U.S., put on an L.A. Dodgers uniform and ignited something called “Nomomania” across the country.

I wrote about Nomo again in 1995 for Time, when that magazine asked me to write an essay about Nomo’s historic migration to MLB, and explain how he was able to circumvent the rules. And I wrote about him yet again in 1998 when I collaborated with agent Don Nomura in a book for Bungei Shunju about his experiences in liberating Nomo, and other Japanese players from the chains that bound them to Japan, in defiance of long-standing NPB custom and tradition. And I would write about him one more time in 2004 when I did The Meaning of Ichiro.

I remember the day Nomura first brought Nomo to my apartment in the Homat Royal next to the U.S. Embassy. I’d seen Nomo on the ball field before in pre-game workouts, and noted that like many of Japan’s top players at the time — Kazuhiro Sasaki, Hideki Matsui, Hideki Irabu — he was physically bigger than most of the other athletes in the game. But I really had no idea how big he was until he walked into my living room. I consider myself a big man at 180 cm and 80 kg. But Nomo seemed to tower over me, His shoulders were as broad as some NFL football players I’d known and his hands were the size of giant hams — rough and calloused giant hams. I’m exaggerating, here, a little, but you get the idea.

We sat for a conversation in Japanese and I was struck by how polite he was and how candid he was at the same time. I’d heard all the negative stories about him, that he was standoffish and uncommunicative, but that was not the way he presented himself to me on that day. He was a friendly, talkative, warm congenial young man. (And it was also apparent that he could understand English better than he let on.)

Among other things, he told me that he although he did not go to the U.S. with the intention of waving the Japanese flag, he did in fact feel the pressure of being a symbol for Japan as the first Japanese star to play in the MLB. He said although he had been treated well, generally speaking, he had gotten occasional nasty letters calling him a yellow monkey and other ugly names (along with letters from Japanese who were still angry that he had left the Japanese game) and that the experience of going to live in the U.S. and playing MLB and helped him understand the feelings of gaijin in Japan better than he did before. “Gaijin no nayami wo yoku wakatte kimashita.” Is what he said.

He had particularly harsh words for the NPB system, saying, “Japanese players can’t reveal their true feeling to the public and that key policies are decided by top-echelon officials who persist in clinging to outdated customs.” He described autumn camp as “practice for the sake of practice … and suggested that it would be more constructive to rest.”

The genesis of this book was an article I had written for Number Magazine after Nomo’s retirement from professional baseball in 2008. Mr. Ken Nishimura of PHP had read the article and asked me if I would consider writing a biography of Nomo’s life. I was initially reluctant, because it would involve a lot of work. But, after giving it some thought, I agreed. I decided I had to do my part to preserve Nomo’s place in history. And I thus began a process of some months of sifting through my old notes and files, interviewing people who had known Nomo at the different stages of his career and doing media searches in the United States.

It struck me that looking back on Nomo’s career, he is the only player I know who came back from the dead three times as a pitcher.

The first incarnation was in the years from 1990-1994 when he was the type of pitcher who would walk the bases full then strikeout the side. All blazing speed and no control. “Doctor K” versus “Doctor Walk.” In one 1994 game, July 1 at Seibu Stadium, he pitched 191 pitches, and walked 16. Prior to that, on Oct. 14, 1993, versus the Chiba Lotte Marines, he threw 181 pitches. On June 12 that same year versus Daiei, he threw 180 pitches. This incarnation of Hideo Nomo was nearly destroyed by a debilitating arm injury in mid-1994 and the Buffaloes suspected he might be finished as a top line pitcher. In fact, after he had a tryout with the Seattle Mariners, before the 1995 seasons, then Mariners manager Lou Piniella rejected him, saying, “He will never make it in the major leagues … especially with that windup.” Fortunately, the Dodgers awarded him a contract and he proved Piniella wrong.

The second incarnation of Nomo was from 1995 to 1997. Nomo had recovered from his arm injury and although the speed on his fastball had diminished somewhat, his unusual windup and his unhittable forkball were enough to make him a winner. As one L.A. commentator put it, “Nomo can do more with his forkball than most pitchers can do with an assortment of pitches.” What’s more he was exceptionally strong and could pitch a lot of innings. He could always be counted on to take the mound every five days. If he had a flaw, it was in his shaky control and the fact that was that his windup took so much time that it was easy for baserunners to steal on him.

But then this: Hideo Nomo suffered another debilitating injury — this time tendinitis in his arm — and Nomo’s pitching prowess deteriorated. In 1998, in fact, Nomo was so bad —2-7, 5.03 ERA — that the Dodgers drew 22 percent fewer fans for Nomo’s starts than others, and even heard booing during some of his starts in Los Angeles that year. At the end of the season, he was forced to undergo arthroscopic surgery on his pitching elbow.

The third incarnation was from 1999-2003, when Nomo returned after being cut loose first by the Dodgers and then the Mets and the Cubs. This time he was wearing the uniform of the Milwaukee Brewers and was now more of a finesse pitcher. His forkball did not move as much as it once had, and some people thought he tipped off his curve when he threw it. Moreover, he allowed an alarming 41 stolen bases, steals, But, miraculously, over the course of the 1999 season in Milwaukee, his velocity returned from the 80’s to the low 90’s. He went on to pitch for Detroit, then Boston and then returned to L.A., morphing into one of the most durable, reliable pitchers in MLB, using guile and experience, along with this fastball and forkball, to prevail.

Then, one could say there was a final incarnation. That was after Nomo fell completely apart, was banished to the minor leagues and wound up in Venezuela. Everyone thought he was finished, but he somehow clawed his way back and managed to get a tryout with Kansas City and, incredibly, make the team — if only for a couple of months. It was one of his most memorable accomplishments, in my opinion.

He was simply a player who did not understand the meaning of quit.

To me, coming from the United States, the Nomo story conjures up the American Dream of the pioneering foreigner who arrives far from home, starts out as an underdog and member of a minority, works hard and makes good. That is the philosophy that America was built on.

Nomo also broke racial and ethnic barriers, furthering the integration of Japanese into American society and helping to bolster the confidence of his fellow countrymen back home vis a vis their Trans Pacific partners. In the process he became a socially important figure in modern history.

The irony of the Nomo experience, of course, is that Hideo achieved far more in Japan by going to the U.S. than he would have if he had stayed. Had he remained with lowly, unpopular Kintetsu, he never would have been a presence on national television in Japan, as he later became with NHK when he joined the Dodgers, and he never would have had those huge endorsement contracts he earned with Nike, IDC, Kirin, Toyota and Sumitomo Life Insurance.

American Dream indeed.

* * *

A number of people helped me in the making of this book. I’d like to give special thanks to Kozo Abe, Daigo Fujiwara, Masayuki Tamaki, Gen Sueyoshi, Trey Hillman, Midori Matsui and Kiyondo Matsui. And also thanks to Mr. Yasuhiko Aida of Bungei Shunju and Mr. Ken Nishimura of PHP, without whom this book would not exist. A version of the book was first published in English in 2017 with Japanime, with thanks to Glenn Kardy,

I revised and expanded this book, updating it with new material, for publication in 2022 on Substack, with thanks to Jack Gallagher.

Great! I’m looking forward to reading the entire book.